Zora Neale Hurston Biographer To Discuss Long Lost Slave Narrative

“Barracoon: The Story of the Last ‘Black Cargo’” will be discussed as part of “Revival: Lost Southern Voices” — a two-day celebration of lost and underappreciated Southern writers.

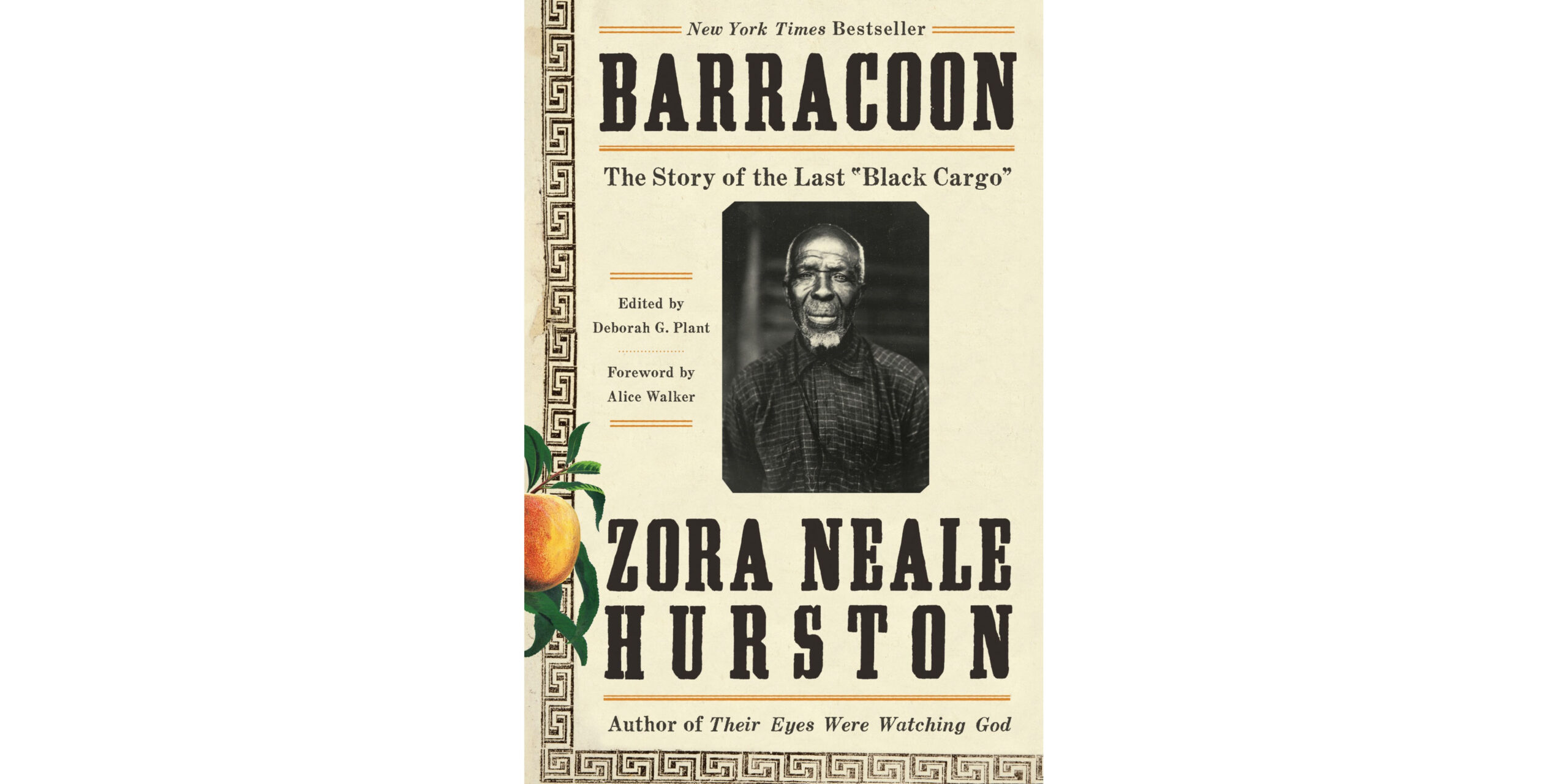

Courtesy of Harper Collins Publishers

In 1860, a teenager living in present day Benin was kidnapped, put aboard a ship, and crossed the Middle Passage to become a slave in Mobile, Alabama. Decades later, Cudjo Lewis, born Oluale Kossola, told his story as the final survivor of the last slave ship to arrive in the United States to Harlem Renaissance author Zora Neale Hurston.

More than 80 years after that, the resulting book “Barracoon: The Story of the Last ‘Black Cargo’” finally saw publication.

That text will be discussed as part of “Revival: Lost Southern Voices” — a two-day celebration of lost and underappreciated Southern writers. Festival co-director Pearl McHaney and Hurston biographer Valerie Boyd spoke with “City Lights” host Lois Reitzes about the book and event.

“Hurston scholars have known about the manuscript for years. It was part of her archives at Howard University,” Boyd says. “What kept it from being published in 1931 when Hurston finished it, was the racism in the publishing industry at the time. Publishers were skittish about publishing it largely because of the subject matter—of the survivor of a slave ship. And they were frightened away by the language of the book.”

Hurston was told by one publishing house that they would be happy to take the book if she made one change: get rid of Kossola’s dialect which the story is largely told in, and replace it with standard English. Hurston refused.

Boyd, who authored the biography “Wrapped in Rainbows: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston,” calls “Barracoon” a gift.

“Kossola was a free man in Africa,” she explains, “he was captured, he survived the middle passage, and he survived several years as a slave, and then he became a free man in the States who helped to found Africatown—a community in Mobile, Alabama.”

“So Kossola for us—for African Americans—he’s like our collective great-great-great-great grandfather.”