Black descendants of 1912 Forsyth racial cleansing say many white residents still in denial

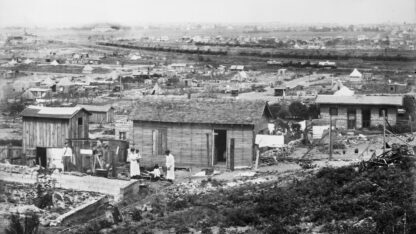

In Forsyth County, about an hour drive from Atlanta, there exists a void. It’s so deeply rooted and ingrained that it’s hard to know just how deep.

While the void’s origins date back long before 1912, that’s when two separate but similar events forever changed the county.

It’s when murderous white mobs known as the “Night Riders” drove out every Black person: 1,098 according to the 1910 U.S. Census Bureau — gone. In the process, they set fire to Black-owned businesses and churches in Forsyth and publicly lynched three men, amid a series of alleged rapes of white women.

More than a century later, fewer than 5% of the quarter-million people who live in Forsyth are Black. Those numbers point to just how effective the racial cleansing really was, and remains.

This Black History Month, U.S. Rep. Carolyn Bourdeaux of Georgia introduced a resolution that condemns the notorious purge of Forsyth’s Black community and calls for a national day of remembrance for the victims that were lynched in an atmosphere that historians have compared to a public fair: Rob Edwards, Ernest Knox and Oscar Daniel.

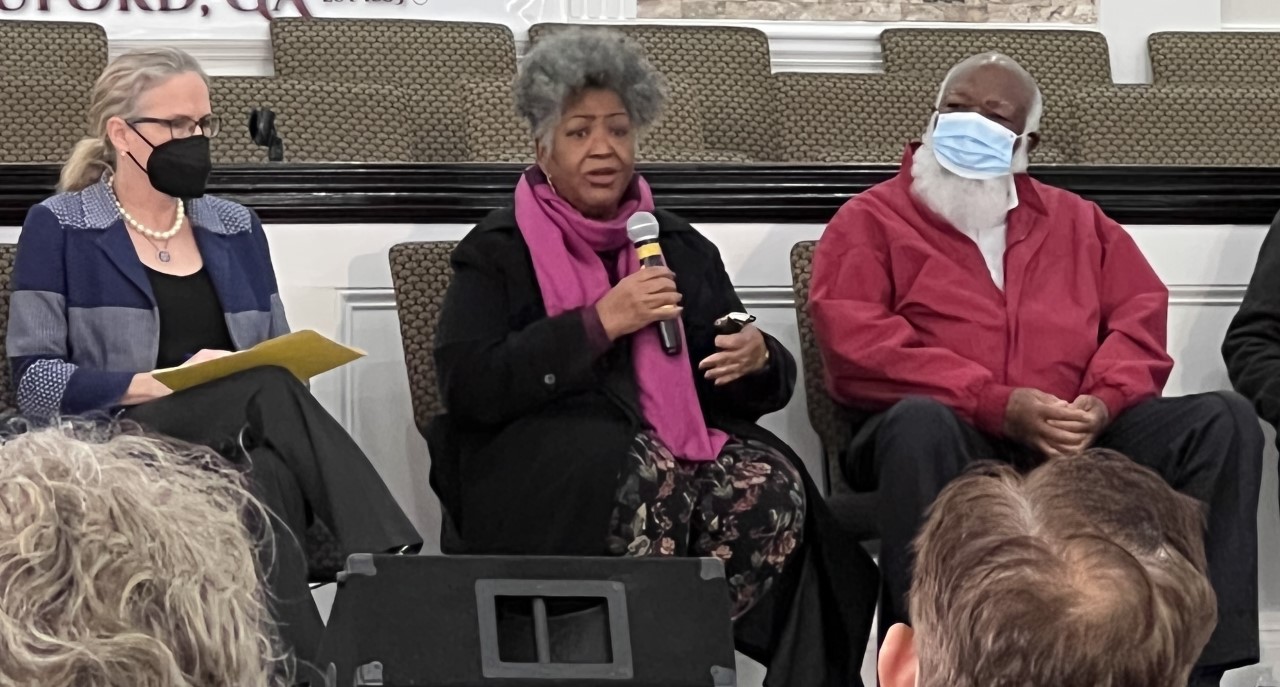

WABE’s “All Things Considered” team went to Poplar Hill Baptist Church in nearby Buford to hear from descendants. The effect of generations of families not coming back — and not even talking about the massacre — makes finding descendants difficult.

Many of Poplar Hill’s 13 rows of pews — seats that have long served as a refuge for those fleeing racial oppression — sat empty or nearly empty.

But during a discussion that was supposed to reckon with Forsyth’s past, there were still moments when white people in the audience — and on the panel — attempted to absolve present-day residents of responsibility.