Baby sea turtles battle rising seas on Georgia's coast

This coverage is made possible through a partnership with WABE and Grist, a nonprofit, independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future.

Sea turtles are wrapping up their annual hatching season on Georgia’s beaches. After a strong summer of nesting, they’re hatching at a rate slightly below average due to predators and rising seas.

Loggerhead sea turtles — the most common in Georgia — are considered threatened in this part of the world, though their numbers have been improving in recent years thanks to conservation efforts.

This year, loggerhead females hauling themselves up onto Georgia beaches achieved their third-highest nesting season on record, laying more than 3,400 nests.

That’s fewer nests than last year, but that’s OK, said Mark Dodd of the Department of Natural Resources, the coordinator of the state’s sea turtle program.

“We’re more interested in sort of the long-term trend in nesting,” he said. “And so in this case, the long-term trend shows about a 4% increase in nesting over the last 35 years.”

But the baby sea turtles in those nests face long odds to survive. Predators love to eat the eggs before they even hatch, and seawater can swamp the nests. On average, only about 60% of Georgia’s sea turtle eggs successfully hatch.

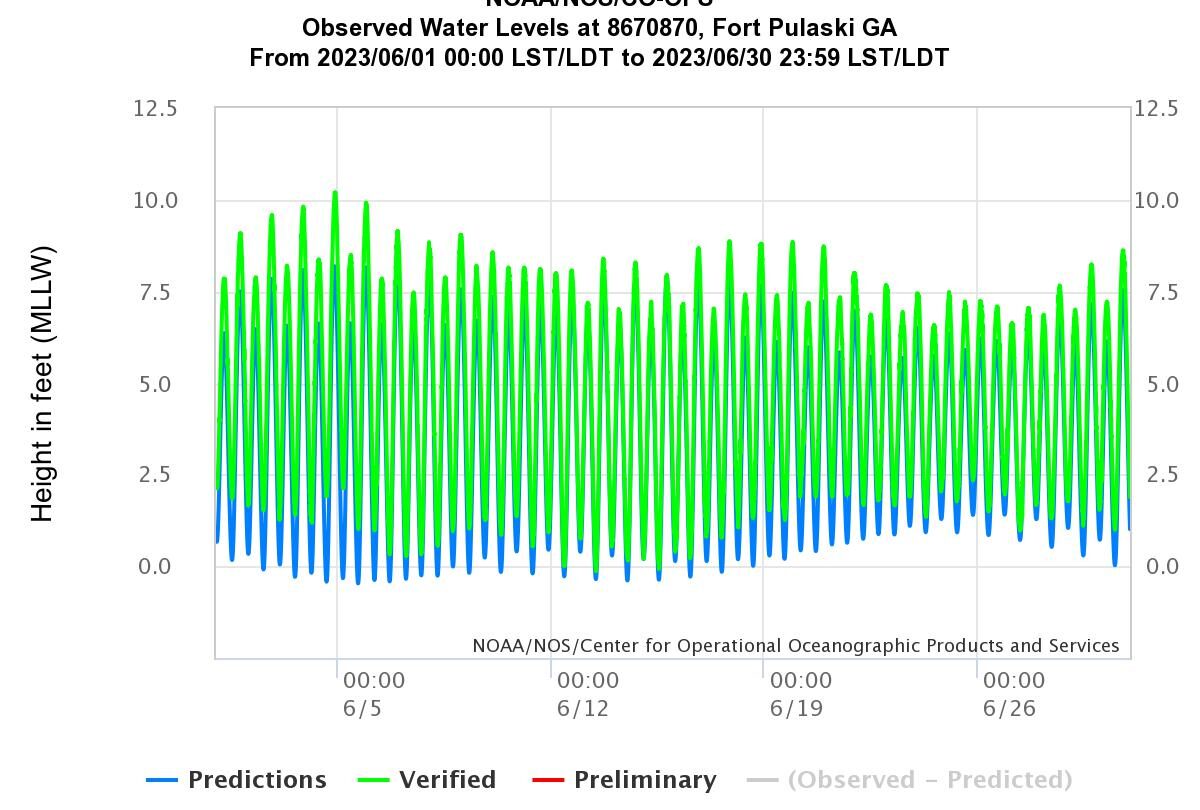

Dodd said that number is down slightly this year, to 55%, partly due to tides coming in higher than predicted.

“That’s one of the issues that we have is that sea level seems to be rising a little faster in Georgia than some other places on the Atlantic coast,” he said.

Trained turtle experts relocate nests out of range of high tides, but if the tides defy forecasters, some nests still get swamped. As climate change causes sea levels to keep rising, those unexpectedly high tides are getting more common.

But there is good news for Georgia’s turtles. Dodd said many of the state’s beaches remain undeveloped, which allows the barrier islands along the coast to change shape naturally and for the sand to shift from island to island.

“As long as the sand sharing system is working, and there’s plenty of sand in the system, as sea level rises we’ll always have beaches,” he said. “They might not be in the same place, they might move landward or seaward, but there’ll always be places for turtles to nest on those undeveloped beaches.”