Coastal Georgia communities prepare as sea level rise accelerates

Sea level rise is accelerating, according to a report released Tuesday by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. It finds coastal communities can expect more flooding and worse storm surges in the coming decades as sea levels rise, on average, 10 to 12 inches by 2050.

Coastal Georgia communities have been planning for this, according to Jennifer Kline, coastal hazard specialist with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

“We have always encouraged them to plan with a range in mind,” she said. “Realistically, most of our communities are already looking at the numbers that were put out in the report.”

Brunswick is working on its stormwater system, which is susceptible to higher tides. Camden County and St. Mary’s have an app where people can see their flood risk and learn how to reduce it. Tybee Island, which Kline called a “highlighted community” because of its high risk as a low-lying barrier island, adopted the state’s first sea level rise plan in 2016. Every coastal county has a disaster recovery and redevelopment plan.

But planning for rising seas doesn’t mean the coast is ready.

This work is expensive. And while Kline said federal funding is available for projects to protect the coast and mitigate damage, it’s not easy to get that money.

“Having access to it could potentially be another obstacle,” she said. “You have to have somebody on staff who’s familiar with grant writing and procurement. And our local governments don’t always have that capacity.”

That’s especially true for smaller communities that have to compete with bigger, better-resourced cities for funding.

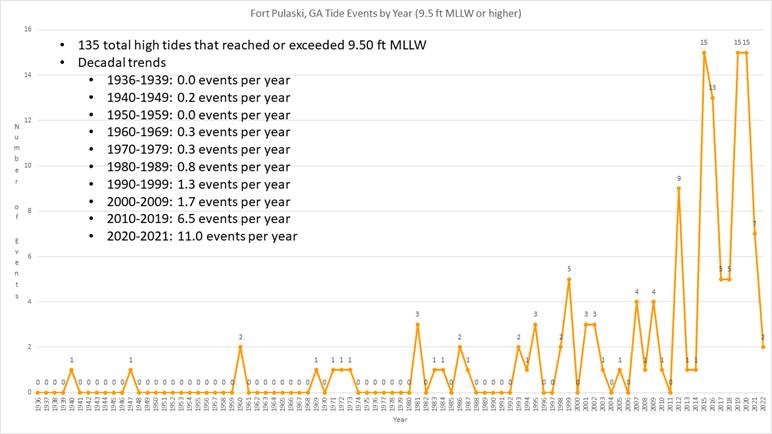

DNR tries to help connect local governments with federal funding, as do other agencies like the Chatham Emergency Management Agency. It’s worked with Georgia Tech to install sea level sensors, which are amassing real-time data about flooding and increasingly high tides, and their impact on local infrastructure.

CEMA Assistant Director Randall Mathews said that information has proven essential.

“Data drives the decision-making process,” he said. “So the more accurate localized data we can get, the better off we are.”

The federal report predicts more frequent flooding in coastal areas, which, as seas rise, will put more coastal residents at risk — a danger the report highlights in county-by-county snapshots. In Chatham County, for instance, one-third of the population lives in flood-prone areas, even before the expected sea level rise.

Mathews said CEMA, which responds to disasters and handles hurricane evacuations, is planning for the at-risk population to increase.

“The only thing we can do is kind of strengthen the community capacity to deal with these things by, you know, whether folks elevate their homes, or we improve infrastructure around it,” he said. “We have several communities here that could get isolated during a high flood event, a high tide event.”

The federal report also looks at the economic impact of sea level rise. It identifies nearly 2,500 Georgia businesses at risk from current flooding, with another 1,900 potentially at risk as the sea level keeps rising.

And it looks at the financial hit to homeowners and communities. In Chatham County alone, the National Flood Insurance Program paid out $78 million in flood insurance claims between 1991 and 2020 — most of that from 2016 to 2020, when the area experienced flooding from hurricanes Matthew and Irma.

For all six coastal Georgia counties, that figure climbs to $131 million.

The report notes that communities share that cost via lower property values, which affect tax revenue.

Kline said the data highlighting business and financial impacts might give some coastal leaders new perspective on the problem.

“That information will be extremely helpful for decision makers and understanding a little bit better about what the economic impact will be to the coast,” she said.