Michael, Irma, Matthew: Three Years Of Storm Damage Test Georgia

Hurricane Michael caused a tremendous amount of damage: agriculture suffered more than $2.5 billion in losses, according to University of Georgia economists.

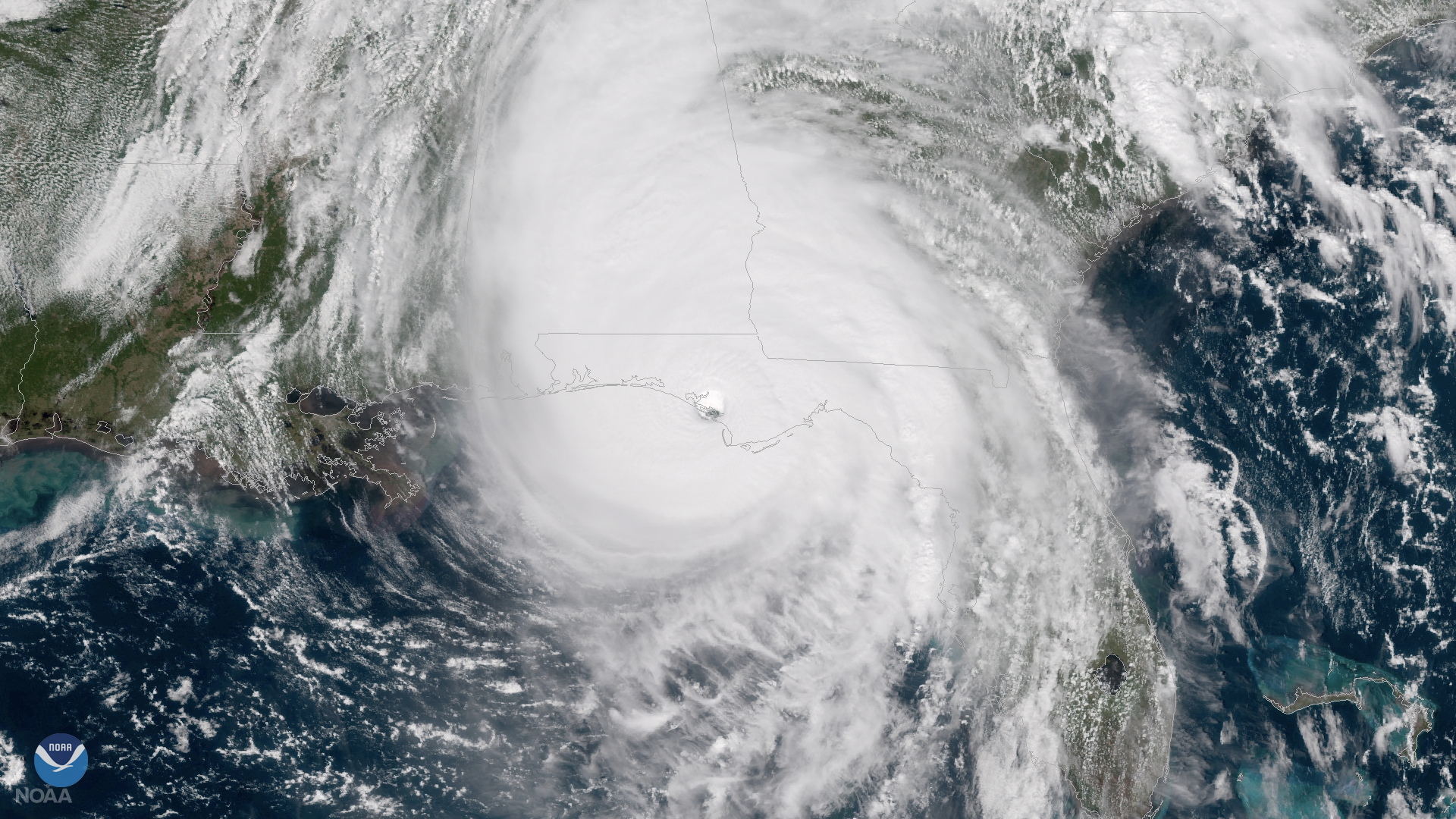

NOAA

The Georgia legislature begins a special session on Tuesday to help areas of the state that were hit hard by Hurricane Michael.

Last month’s hurricane caused a tremendous amount of damage: agriculture suffered more than $2.5 billion in losses, according to University of Georgia economists.

House Speaker David Ralston said last week that the state legislature will initially focus on providing money to communities to repair infrastructure and to clean up debris. The federal government is responding, as well, with emergency assistance from both FEMA and the USDA. So far, FEMA has approved more than $8.8 million in grants to households.

Hurricane Michael is the latest in a string of hurricanes to affect Georgia in the past few years, and there could be more, going against an increasingly false-feeling theory that Georgia doesn’t get hit much by hurricanes because of the concave shape of the coastline.

Before Michael was Irma, a tropical storm by the time it hit Georgia, but still disastrous for some coastal residents when it hit in 2017. Before Irma was Matthew, a 2016 hurricane that also did damage.

“If you look back over the history of hurricanes that have affected Georgia you know we’ve gone through periods where we haven’t had a whole lot going on,” said Pam Knox, interim director of the Georgia weather network and an agricultural climatologist at UGA. “Now we’re in a more active period.”

In the late-1800s Georgia got hit by a few hurricanes, and though there had been a century-long pause, Knox pointed out that Georgia is susceptible to hurricanes from two directions.

“When you look at Georgia we’re kind of right in the crossroads because we’re both on the path of Gulf of Mexico storms that can come in from the south and then crossover like Michael did,” she said, and also on the path of storms in the Atlantic Ocean that carve up the east coast; that’s what Matthew did.

“One thing people ask is, ‘Are we going to have more hurricanes as the climate gets warmer,’ as it certainly has been doing since at least 1970,” Knox said. “The short answer is that scientists really don’t know.”

That is, they don’t know if any given place will get more hurricanes. That’s kind of like a roulette wheel, said Kim Cobb, the Georgia Power chair of earth and atmospheric sciences at Georgia Tech. But there is evidence that a warmer climate and warmer oceans, have an effect on hurricanes themselves, said Cobb.

“There’s a really strong suggestion that climate change is already tipping the scales towards stronger storms,” she said.

Storms like Harvey and Florence could become more common in a warmer climate, made bigger and wetter by warmer air and warmer oceans.

Cobb said policymakers should be thinking about the effect of climate change on their communities, not just from hurricanes, but drought and sea level rise, too.

“These are the kinds of tough questions that policymakers and community leaders need to be asking themselves. What is their responsibility to help their communities prepare for not just the climate of the future but the climate of now which has already changed profoundly from the climate of the last decades,” she said.

South Georgia farmers will bounce back, Knox said; they’re tough and resourceful, but they may have they have to adjust.

“Agriculture is going to continue to be a powerhouse here in Georgia,” she said, “but I think farmers are going to have to learn to be flexible and they’re going to have to find new ways to be resilient.”