In 1971, Cathy Bradshaw was 23 years old. She had just finished her master’s degree in Urban Studies from Brown University and the $200 a month lease for her Ansley Park apartment was about to be up because the home was put on the market for $87,000.

There was no way she could afford to buy it. She didn’t have a job and recalls only having $800 in her bank account.

Bradshaw thought about moving to Inman Park, where two of her closest friends had just bought a home for a mere $5,000.

At the time, many of Inman Park’s grandiose Victorian mansions had been demolished for a proposed highway and the ones that were left standing had been carved up into apartments.

The crime rate was high and the neighborhood had an industrial zoning designation that discouraged families from owning homes. Cars were parked on lawns and were often tied up to trees. Potential homeowners were redlined.

On their way out of town in June 1971, Bradshaw’s parents had warned her not to rent an apartment in Inman Park while they were gone.

Bradshaw agreed. She kept her promise and and didn’t rent an apartment in Inman Park that weekend. Instead, she bought a house.

She put the $800 she had in her bank account toward a down payment and assumed the previous owner’s $19,000 mortgage which left her paying $84.72 a month for a two-story home.

“So I had no car, no job, but I owned a house,” Bradshaw remembers.

The night she bought her home, someone set a car on fire in front of her house because of argument with a tenant. Despite the chaos in 1971, Bradshaw’s neighborhood had once been vastly different. It was originally designed for Atlanta’s elite.

In 1884, Joel Hurt dreamed of developing an exclusive residential suburb of Atlanta. Frederick Law Olmsted had already designed Riverside outside of Chicago and slowly but surely planned suburbs began sprouting up around the country.

With the financial help of Samuel M. Inman, a wealthy cotton merchant, Hurt started buying up plots of land in an oak grove surrounded by a few cottages and farmhouses two miles east of downtown for what would become Atlanta’s first planned residential suburb: Inman Park.

This suburb was designed to be grand with the hopes of attracting Atlanta’s wealthiest and most influential citizens. Winding streets wrapped around Olmstead-inspired parks and the homes would sit on generous lots.

Hurt, and the 28 shareholders of his East Atlanta Land Company that had interest in Inman Park, even worked to widen an east to west corridor called Foster Street to provide direct access from downtown to Inman Park.

In 1888, after holding more than 500 meetings and demolishing 94 buildings, they opened a two-mile, tree-lined thoroughfare called Edgewood Avenue.The next year, a few months after Hurt sold the first lots in Inman Park, a yellow car with an oak interior from the Atlanta and Edgewood Street Railroad Company made its first trip down Edgewood Avenue, connecting the suburb to downtown in a quick 15-minute trip that only cost a nickel.

There was initial excitement about the suburb. After that first auction of lots, the suburb was lauded “a perfect place of residence” and it attracted some of Atlanta’s most prominent families, including Asa G. Candler, Ernest Woodruff and former Governors Allen Candler and Alfred Colquitt.

But, Inman Park’s peak didn’t last very long.

According to historian Richard Beard, money became more important to the East Atlanta Land Company than holding true to the original plan for the neighborhood.

More homes were being built to make up for a decline in lot sales and public spaces started to dwindle. Smaller homes were built as infill.

The wealthy families originally attracted to the neighborhood started moving further north and northwest and by 1920, only four people in Inman Park still lived where they had at the turn of the century, according to Beard.

Inman Park was complete by the time of the Great Depression, but as Atlanta’s population grew, more people needed to crowd into the existing residences and owners subdivided their homes to bring in more money.

Many of these grand Victorian homes stayed subdivided and leased out until Inman Park’s renaissance.

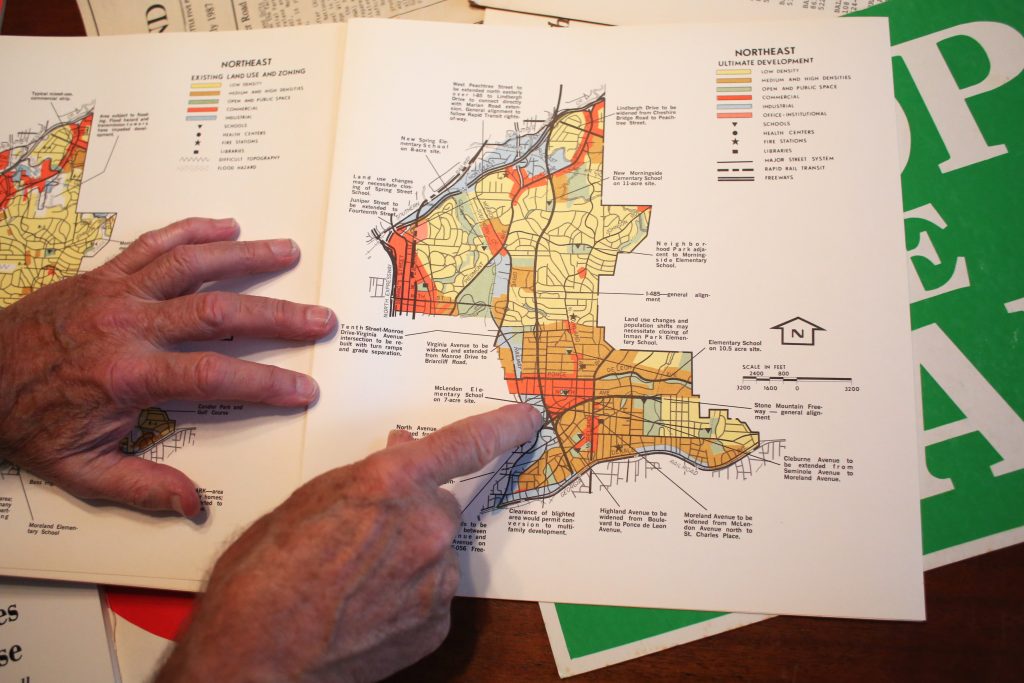

By the 1960s, it was a risk to invest in Inman Park. Not only had the Victorian homes been subdivided into tenement buildings and fallen into disrepair, but also a freeway was planned to cut through the neighborhood.

The city of Atlanta was tearing down homes to make room for the road. But by the early 1970s, around 35 young residents bought homes in Iman Park in protest. If they owned land, they might be able to stop the freeway.

Cathy Bradshaw remembers being the only single female at the first meeting of Inman Park Restoration in the summer of 1971, the year she bought her home.The neighborhood’s newest residents, soon to be known as the Inman Park Pioneers, banded together.

“There were a lot of Northern transplants,” Bruce Maclachlan recalls, “We were new to Atlanta and we didn’t share the prejudice of white Atlantans against the intown neighborhoods.”

Whenever someone new would buy a home, the neighbors would come over and help them paint their house and garden. There were potlucks on Fridays and everyone shared tools because they were too poor to buy their own. They worked to clear Kudzu and pick up trash from the vacant spaces around their neighborhood.

While the community was bonding, Bradshaw’s house was still slated to be an off ramp in the proposed Hurt Street expansion.

The city had already demolished 554 homes by 1971 to prepare for Interstate 485, that would run north to south, cutting directly through Morningside, Virginia Highlands and Inman Park, and eventually intersect with the Stone Mountain Tollway that would run east from downtown and cut through the neighborhoods that fed into Bass High school, including Poncey Highland, Inman Park, Little Five Points, Candler Park and Lake Claire.

These neighborhoods banded together within BOND, the Bass Organization for Neighborhood Development, committed to improving the residential neighborhoods and fighting off the road.

Inman Park residents even adopted a symbol: a butterfly that embodies Inman Park’s renaissance, with the outline of a face looking to the left: the past, and the right: the future. Neighbors proudly display this icon on the neighborhood banner hanging on their doors and front porches today.

The residents fought the road on all fronts. They protested, filed lawsuits and organized politically. In ’71, a judge ruled in favor of the neighborhood, requiring an environmental impact study to be completed on the proposed road and its impact on the neighborhood.

In 1972, then-Gov. Jimmy Carter stopped the construction of the Stone Mountain Tollway, but the intown residents knew the fight wasn’t over because the Department of Transportation still owned the 219 acres intended for the road.

With the funds raised from their annual festival, the residents of Inman Park hired lawyers and slowly started tackling their own problems. As long as the Department of Transportation owned the land, Inman Park wasn’t safe.

Today, thousands of people flock to Inman Park’s annual festival during the last full weekend of April each year. What started with a candlelit tour of the dilapidated homes being restored by pioneers in the 1970s to spark revitalization efforts and attract more homeowners has become a curated tour of the neighborhood’s most beautiful homes. People dress up for the parade and listen to live music.

The neighborhood was zoned for high-rise apartments and industrial buildings, as if in preparation for the road.

Holly Mull spearheaded the efforts to down-zone Inman Park to low-rise apartments, single family homes, and duplexes. Mull was successful in 1973, the same year Inman Park was included on the National Register of Historic Places — another key strategic move in the fight against the road. This historic designation would offer them protection.

At the same time Inman Park and the northeast neighborhoods were fighting off the proposed Interstate 485, neighborhoods in southwest Atlanta had their own freeway battle. Residents in intown neighborhoods were demanding a voice and taking stand against what was happening in their neighborhoods.

The political organizing in these neighborhoods was so effective, that when Maynard Jackson was mayor elected in 1973, he changed Atlanta’s charter from an Alderman system to the Neighborhood Planning Unit system that exists today, to allow neighborhoods to be informed, included and empowered in the development of the city.

“Communities didn’t have a voice, and they didn’t know about the freeways,” Inman Park resident Joseph Drolet and founder of Virginia Highland Civic Association explains, “So we created a voice and that voice still exists today.”

In 1974, all planning for the highways was suspended indefinitely. It seemed as though the neighborhood had won.

Today, Inman Park is known for its cafes, its restaurants and its access to the BeltLine. The Victorian homes are still standing and meticulously taken care of, but most people walk around Inman Park’s downtown area on Highland Avenue where many young professionals reside in condos and apartments that overlook trendy restaurants, boutiques and bars.

Electric scooters and blue bikeshare bikes wiz past pedestrians. The area is bustling. Inman Park is considered one of Atlanta’s premiere neighborhoods with homes selling for more than $1 million.

A few blocks over from Highland Avenue, the former Atlanta Stove Works factory was turned into the mixed-used development of Krog Street Market.

Visitors can grab a beer and choose to eat from one of the many food stalls before browsing various shops or walking over to the BeltLine.

While it’s a different feel than Joel Hurt had originally intended, the dedicated residents and pioneers of Inman Park were involved in how their neighborhood developed into what it is today.

They withheld agreeing to zoning changes and worked with developers to design something they could be happy with. Their culture of militant involvement still thrives.

Joseph Drolet is one of those residents that has been involved in the neighborhood for more than 40 years. He bought a home without plumbing, heating or a roof in 1977 and has lived in Inman Park ever since.

“The sense of community is unlike almost any other neighborhood I’m aware of because of that fact that it was a siege mentality. We had to stick together and be looking out at the perimeters and be looking out for threats in the neighborhood,” Drolet said.

Those threats might have been burglars, threatening zoning restrictions or they might have been freeways. There was a feeling that the neighborhood would cease to exists of they didn’t do anything.

Their reaction was to take everything into their own hands.

John Sweet, a dedicated Inman Park pioneer, started a credit union to compete with the banks that were redlining intown neighborhoods. When police officers wouldn’t take car break-ins seriously, Drolet, a lawyer who worked at the District Attorney’s office, worked to get them qualified as a felony instead of a misdemeanor. Neighbors ran for political office and hosted fundraisers in their Victorian mansions.

Amidst the chaos, there was a sense of community and survival. We have to work together,” Drolet said.

At that time, the freeway was still a threat. Andrew Young was elected mayor in 1981. He had campaigned on a pro-neighborhood platform, but once he was elected he announced the plans for a new road: a parkway to Jimmy Carter’s new presidential library that would sit on the same land as the freeway that had been proposed decades earlier.

Young pitched the road as a rolling parkway, designed like Rockcreek Parkway in Washington, D.C., but the intown residents immediately understood that this was another iteration of the expressway they had been fighting for years.

The odds were against the residents of Inman Park because now Atlanta had a mayor that supported the road and the Department of Transportation still owned the land that cut through the BOND neighborhoods. Despite all of that, the residents worked politically, legally and administratively to fight the road.

“Any form in which we could work, we worked.” Drolet said.

They had people follow Jimmy Carter all over the country and picket wherever he was raising money for his library. They filed different lawsuits in the Superior Court of Dekalb County and Fulton County and even in federal court.

They used environmental laws, historic laws and had the National Register to hold a hearing.

By 1984, the residents had run out of options. “We had played a lot of our legal cards and we were running out of things to sue about and courts to sue in,” Drolet explains. With no more lawsuits, the city was slated to start construction.

The residents protested. They pitched tents and chained themselves to trees. Midge Sweet remembers being pregnant while protesting a bulldozer. The residents of Inman Park continued to protest and fight throughout the 1980s, and they eventually stalled construction for so long that they had waited out the pro-road politicians’ terms.

Maynard Jackson was elected mayor again in support of the neighborhoods and there was a new transportation commissioner.

The residents banded together and demanded a say in the design of the road that would border their neighborhood. Cathy Bradshaw spent 54 hours mediating with the City of Atlanta and with the residents that would be impacted.

President Jimmy Carter did eventually get a road to connect to his library, but the residents got what they wanted as well. When construction started in 1991 on Freedom Parkway, they knew they were getting a real parkway that served the library flanked with parks and running trails on either side, rather than the expressway with brown pavement that had originally been proposed.

Civil War battles were fought here. Zoning battles were waged here. Neighbors fought slumlords and rampant crime, and for more than three decades they fought an expressway that would slice through their neighborhood.

Today, runners, pedestrians and cyclists use the parkway almost as much as cars do. There is a bend in the road and a 35 mph speed limit. There is a farmer’s market is held at The Carter Center every Saturday for the residents of the surrounding neighborhoods. There are no raised exits or gas stations next to homes.

In the mid 1990s, after years of fighting the road, Joseph Drolet went to an Inman Park neighborhood meeting on a whim. Wedged between seemingly mundane announcements, someone mentioned that the Department of Transportation had transferred the highway land back to the City of Atlanta to be become parkland.

The 210 contentious acres surrounding the parkway were finally free from ever becoming a real freeway. Drolet looked around and quickly realized that no one in the meeting understood the gravity of what that meant.

Choked up, Drolet managed to muster, “For 25 years, we’ve been fighting this road and the only way we would know if we won was if we got the land back.” After more than two decades, they finally did.