Right whale advocates appeal to boaters to protect endangered species

This coverage is made possible through a partnership with WABE and Grist, a nonprofit, independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future.

The scientists and advocates racing to save North Atlantic right whales are trying a new approach this season: warning boaters that hitting a whale could sink their boat.

Educating ordinary boaters and convincing them to slow down and watch for whales is a key step in protecting right whales – an effort that also includes coordinated tracking and monitoring, restrictions for large vessels and an ongoing battle over lobster fishing in the Northeast.

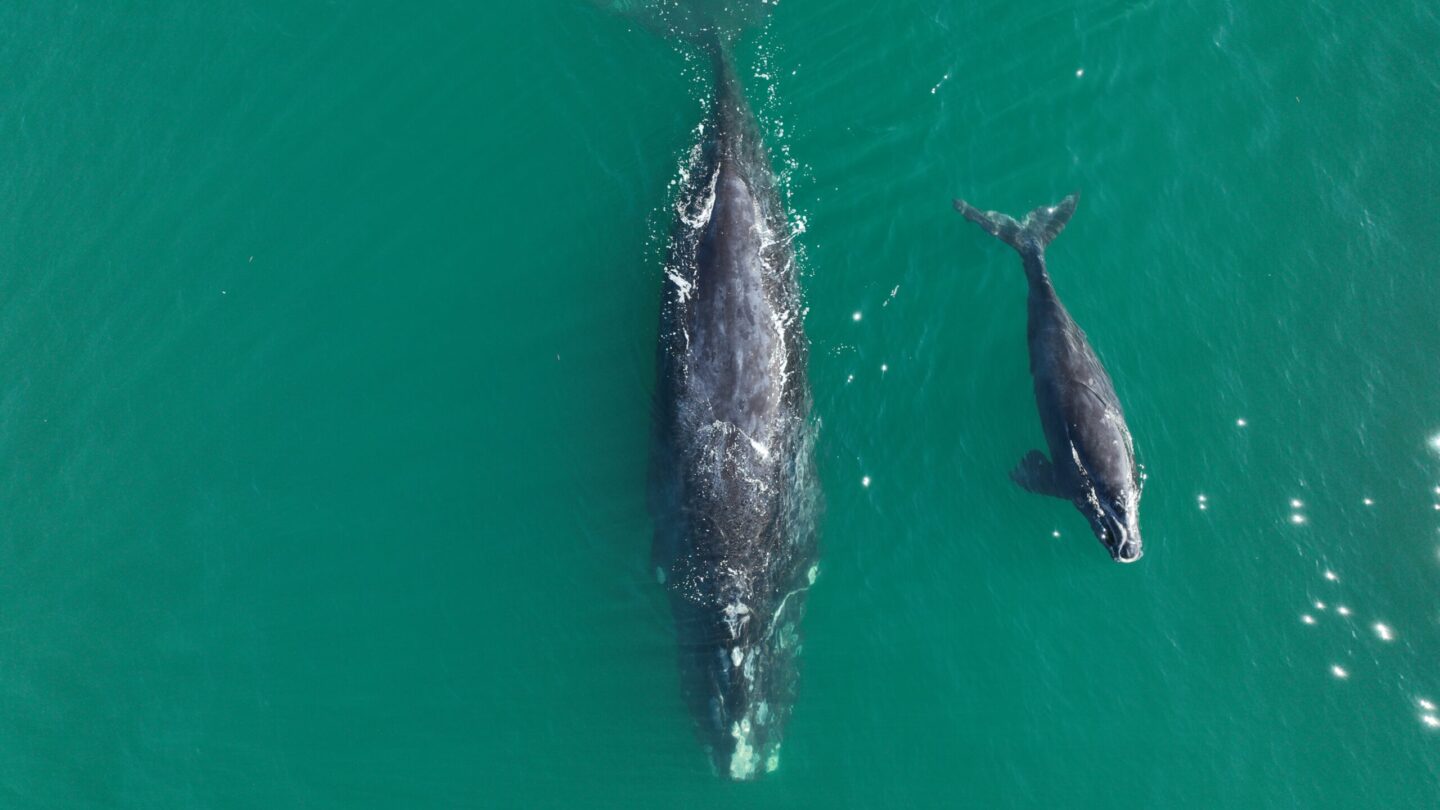

North Atlantic right whales travel to the waters off Georgia, Florida and the Carolinas each winter to have their babies. With fewer than 350 of the whales left on the planet and fewer than 100 of those being breeding-age females, every single baby counts.

Last year, a 54-foot fishing boat off Florida injured a mother whale and killed her calf.

In the Southeast, vessels over 65 feet – like the container ships calling at Georgia ports – are supposed to follow a speed limit during calving season to avoid injuring or killing whales. However, most fishing boats are too small to fall under that speed rule. But they’re still plenty big enough to kill a whale, especially a calf, like the one off Florida’s coast.

“If you don’t know what you’re looking for, you might hit it,” said Tybee Island charter fishing captain Judy Helmey.

She’s been fishing off the Georgia coast for more than half a century and remembers when there were a lot more right whales in the water – and there weren’t yet laws requiring boats to keep their distance.

“So we would just cut our engines off and just drift with them,” she recalled.

Now, the whales are in the midst of an “unusual mortality event” that began with a spike in deaths in 2017. The leading causes: heavy fishing gear, especially the kind used for lobstering in the North, and people hitting the whales with boats, including small ones.

Since 2004, there have been five highly-suspected strikes of right whales by boats under 65 feet, according to Clay George, a wildlife biologist with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. The whale’s fate isn’t known in every case, but “the boaters saw big pools of blood in the water,” he said.

“Most people don’t know that we have whales here,” Helmey said. “They could hit one and harm the whale or themselves. I mean, there could be a lot of damage involved.”

She’s not kidding. The fishing boat that hit a whale and her calf last year nearly sank. The captain had to ground the boat, and it ended up being a total loss – to the tune of more than $1 million.

State officials are stressing this point in a new messaging effort this season. Fliers and emails headlined “Go slow-whales below!” feature pictures of the sinking fishing boat and urge boaters to slow down and post a lookout for right whales.

“One of the things we’ve been trying to convey to coastal boaters is that, you know, keep your eyes open, be careful, and slow down, not just to help the whales but to protect you and your boat and your passengers,” George said. “If you struck a whale offshore out here and started taking on a lot of water, things could get dangerous really really quick.”

Helmey said she thinks that makes sense.

“I think it’ll make them read the whole thing,” she said. “And then maybe they’ll get to thinking, and then they’ll try to figure out a way how they can notice [whales] better. Because you heard it’s sunk a boat that big, you can imagine what it’s gonna do to a small boat.”

From November through March, scientists search the water off the coast of Georgia for whales, too, looking for mother whales and their newborn calves.

When they spot a pair, they photograph it from above with a plane or drone and from a boat with a long-lens camera, operating under a special permit; most boats have to stay 500 yards away from the endangered whales.

“Every single one of these moms is identifiable by the marks on their head,” said George on a recent whale-tracking trip. “The great thing about these new, small quadcopter drones is that we can keep a distance like this, and we can send it over there, and get the images that we need.”

The whales have whitish bumps on their heads and ridges along their lips. Many also have identifiable scars from entanglements or boat strikes that they managed to survive.

George and his colleagues in the right whale effort, which includes Georgia DNR, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Florida Fish and Wildlife, Clearwater Marine Aquarium and the New England Aquarium, have spotted 14 calves so far this winter. They’ve seen female whales in the area without calves, too, so they’re hoping for more.

It’s an improvement: in 2018, no calves were born, and the numbers were low in several of the surrounding years.

Scientists have determined that climate change is to blame. Warmer ocean waters in the Gulf of Maine, where the whales typically feed, caused the plankton population to plummet. The lack of food led to a drop in reproductive rate.

It also drove right whales to look for food elsewhere, including in Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence, where there weren’t adequate protections in place yet. In 2017, 17 whales were found dead, 12 of them in Canada. The country has since put rules in place to protect the whales.

In light of all that, George called the recent uptick in calving “encouraging.” But he said there is a caveat.

“Even if all of them were calving at record numbers, as frequently as they possibly could, the population still wouldn’t grow because of the number that are dying from human causes each year,” George said.

Helmey helps to get the word out through a widely-read weekly newsletter she distributes to boaters, fishing clubs and others on the coast. She includes her old photos of whales swimming like old Hollywood synchronized swimmers, or blowing from their blowholes, or just floating near the surface.

“I have some pictures that are really the coolest. I have the Esther Williams where they put one fin up, go sideways, and then I have ‘em where they’re upside downwards,” she said.

While Helmey has seen the fliers, other coastal boaters said they haven’t. According to DNR, 52% of recipients, or 9,800 people, opened the “Go Slow, Whales Below” email that went out to registered boat owners and saltwater fishing permit holders.

St. Simons Island fisherman Will Owens said he didn’t notice an email from DNR. But he’s aware of the whales – he remembers making a clay model of a right whale in school – and keeps an eye out for them.

“Whoever’s driving the boat, I mean, pretty much their only job is to be looking out in front for trees, logs, other boats, really any obstruction that would cause damage to something else or to our own vessel,” Owens said. “We try to leave no trace, like they say. We don’t want to cause any problems. We want everybody to be safe.”

DNR officials said their outreach effort is just getting started. They hope to set up tables at boat shows so they can get the word out face to face – and ultimately protect boaters and endangered whales alike.