In Piedmont Park, Noguchi's 'Playscapes' are both modern art and a children's playground

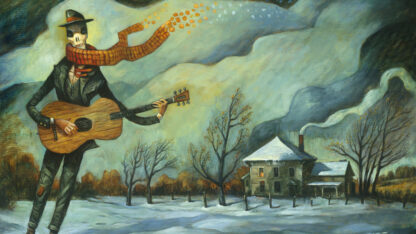

In the heart of Atlanta’s Piedmont Park, a world-renowned work of art by a master sculptor hides in plain sight: a collection of interactive sculptures called “Playscapes” by American artist and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi.

“Playscapes” occupies a distinctive dual role as a large-scale work of modern art and a playground for children. Built in 1976, the construction of “Playscapes” was sponsored by the High Museum of Art and the National Endowment for the Arts as part of an initiative to bring art to public spaces, a move that anticipated many cities’ efforts today.

Noguchi began designing landscapes for children in the 1930s, then produced his first designs for playground equipment in 1940. Throughout the following decades, he made repeated unsuccessful attempts to construct a playground in New York, where he lived at the time.

In 1973, a High Museum volunteer named Frankie Coxe suggested building a children’s playground that was also a work of art. Gudmund Vigtel, then the museum’s director, decided the work would be the institution’s gift to Atlanta in recognition of the national bicentennial in 1976.

Noguchi was always the first choice for the project; a quote from the sculptor about playgrounds was included in a fundraising newsletter before he was officially hired in October 1975. Following a visit to the site in Piedmont Park, Noguchi’s designs for the “Playscapes” were completed by December of that year.

Dakin Hart, senior curator of the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum in New York City, joined “City Lights” host Lois Reitzes via Zoom to talk more about this unique Atlanta treasure.

Interview highlights and more images follow below.

An expression of “art for the people”:

“[Noguchi] didn’t see ‘playground’ and ‘priceless work of art’ as incompatible concepts. He was really interested in making sculpture that played a role in civic life,” said Hart. “[Noguchi] said, ‘Sculpture can be a vital part of our everyday lives if pushed into communal usefulness,’ and he couldn’t think of a better way to push into communal usefulness than to make something that kids could interact with.”

“The most interesting thing about it is [that] it’s Noguchi’s only playground in the United States. It’s the only one that he was able to execute in his lifetime, but [by] the time that it was created in the mid- to late-seventies, Noguchi had been trying for 40 years to get a playground built in New York City, which is where he lived, and had run into all sorts of barriers in trying to do that. So he was extremely pleased and proud to finally come up with the right combination of circumstances to get a playground built,” Hart explained.

Shapes to spark the imagination and invite experimentation:

“That part of Piedmont Park is lovely. It’s not far from the road, and so he did a little bit of contouring… He tried to create a little bit more of the feel of a glen, kind of tucked away in a forest,” said Hart. “Now, your everyday ordinary neighborhood playground may be one that has extraordinarily complicated, very well-engineered and very interestingly shaped playground equipment, which has made Noguchi’s subtler and subtler… They don’t look totally conventional. He’s made them in a particular way, but again, it will look a little bit like a normal playground, just highly attuned.” He added, “But, in part, that’s because he’s had such an impact on playground design.”

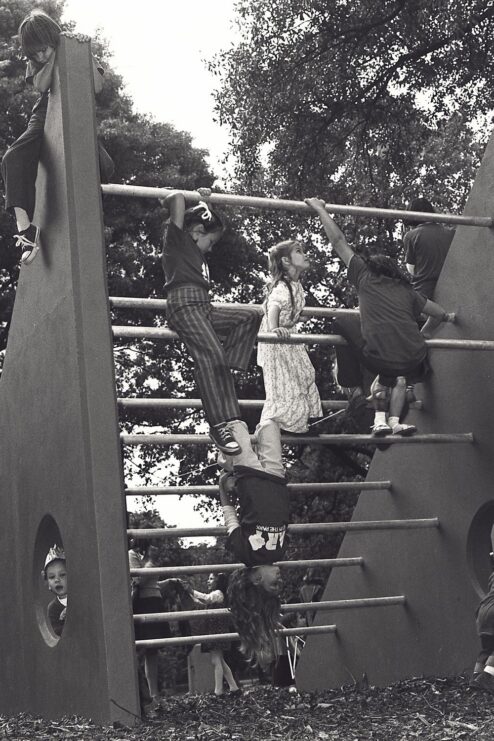

“There is a piece at ‘Playscapes,’ a wonderful piece that uses a piece of playground equipment that he created called ‘play cubes.’ So it’s an arrangement of cubes in a kind of pyramidal shape, and then one in more of an ‘S’ shape, and those are combined together into something that looks a little bit like the ruin of a Mayan temple that you can climb up on and jump off of.”

Isamu Noguchi’s deeply considered theory of play:

“He was interested in very simple shapes because simple shapes are the ones that kids can do the most with in their imaginations. It’s kind of the old joke…You get the super fancy battery-operated whiz-bang kind of toy for your child for Christmas, and they get it, they unwrap the present. There it is… They play with it for two minutes and are bored, and then pick up the box that it came in and end up spending two days playing with the box instead of the toy.”

“The old model that Noguchi was working against was that model of military training equipment; monkey bars and things where you were performing a repetitive activity over and over and over again, to physically internalize it,” Hart explained. “Noguchi didn’t think that playgrounds should be based on that model. He was interested in what he thought of as a non-directive model, more like nature. So here a whole bunch of things that can be used a whole bunch of different ways. Have fun, go crazy.”

More on the life and art of Isamu Noguchi — and the preservation of his work — can be found at https://www.noguchi.org/.